Playful and complex

As Ersan Mondtag makes his Italian opera debut with the double bill of Gianni Schicchi and L’heure espagnole at Teatro dell’Opera di Roma, he explains why he loves the complexity of working in opera, and the importance of team work

How do you go about creating a new opera production?

The music is always the most inspiring influence at first. Then my dramaturg and I read the libretto and look for gaps that allow us to find a concept and to create references. From that, there is the question of the set design, which is the most important part because it defines the staging.

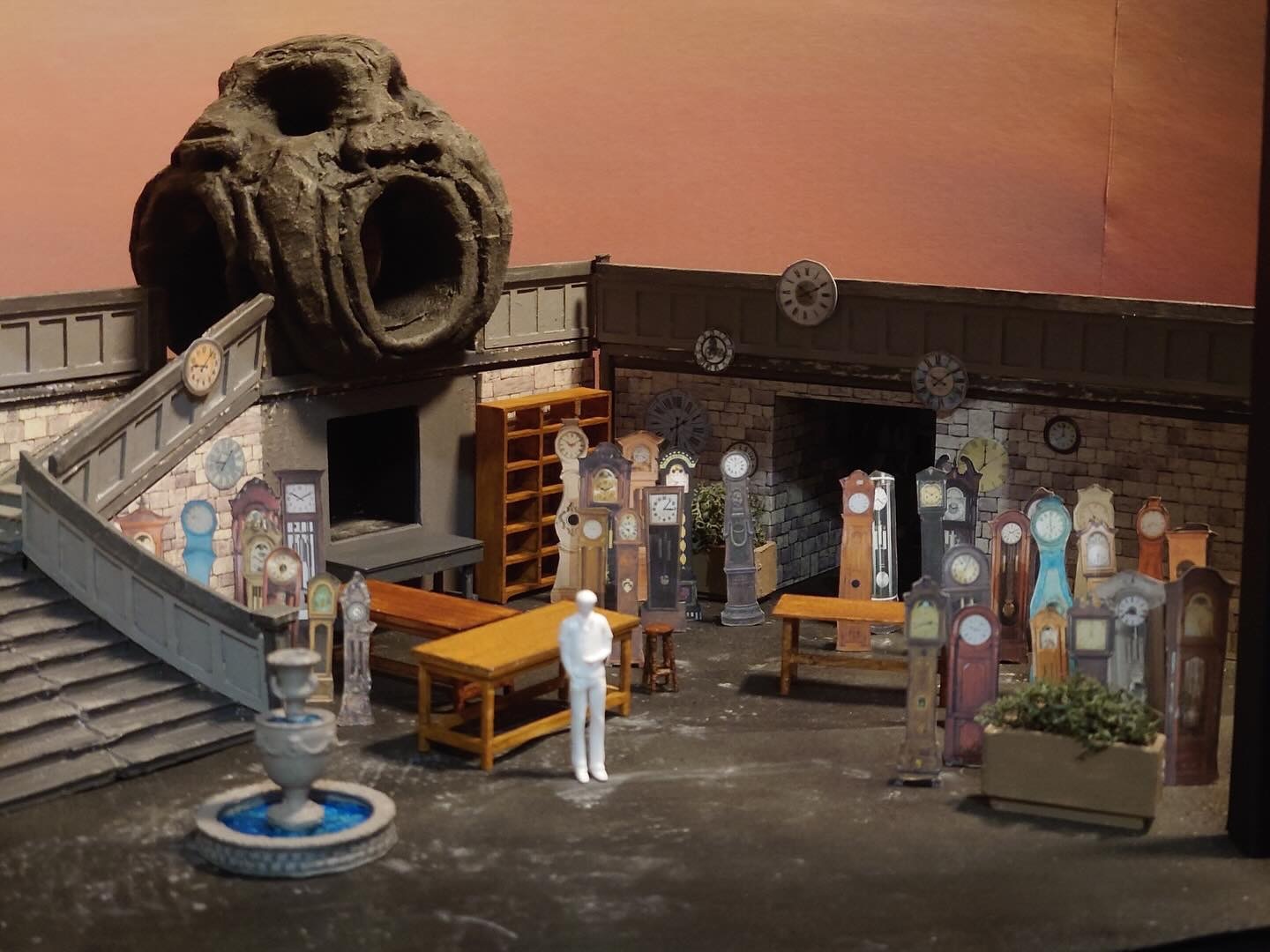

I work with regular associates and usually have several projects on at the same time. For each one, I create models which we use as a playground. The lighting designer comes and we discuss how to light it, and if I’m not designing costumes, the costume designer gets involved. We check the colours and shapes, and at some point, we give it to the theatre to build. It’s a long process and for the first months I only work on the table with my team, with the miniature theatre.

What are your concepts for Gianni Schicchi and L’heure espagnole?

Gianni Schicchi is based on a character from Dante’s Inferno, who is trapped deep inside Dante’s Hell. Puccini’s opera is about a grandfather who is dying, whose family is concerned about how to share out the money. It’s a comedy, but dark. We asked ourselves what Dante’s Inferno corresponds to today – perhaps an apocalyptic world where nature has been devastated. So we decided to stage it not in a luxurious palace, but one that has been destroyed, which nature is taking back. The characters are zombies – dead people who are not even aware that they are dead – trying to find the money to share between themselves, but realising there’s nothing left.

If Gianni Schicchi is apocalyptic, L’heure espagnole is post-apocalyptic sci-fi – the characters look like survivors from the movie Dune. The piece is not particularly political – it’s about a woman betraying her husband by putting him into a clock. The palace is a wreck, the walls collapsed. We can see the universe beyond and pieces of the walls fly through the air. The singers pretend life is normal, betraying each other and simulating a functional planet, because they are in complete denial.

This sense of denial is another motif that connects the two works. The world goes from apocalypse to post-apocalypse and from denial to super-denial. This also means that the stage transforms for the second opera, but mainly stays the same.

What do you enjoy about directing opera?

There are so many people and different groups of artists involved in opera: singers, orchestra, choir, costume and set designers. More than 300 people work on a show in order for it to be performed on one night. They all put in so much effort for just two or three hours of a show. It’s the highest form of art because it brings so many forms together: architecture, fashion, art, music, literature. I enjoy how playful opera is, and the complexity of organising it, which is much greater than with theatre.

How do you work with the creative team?

The most important thing is the team you hire to create the costumes, dramaturgy, lighting. If the team works, it’s easy to create these big worlds. I’m in charge and lead the discussions, but everyone contributes and the concept is created within the entire team. It’s not that I come up with an idea and say, ‘Now work for me’. It’s a team process and a collective concept. I have worked with the same people for more than ten years, so everyone knows what to do and what each other likes so usually we don’t even need long discussions. They just come up with ideas, and I say, ‘Nice, let’s do it.’ My job as director is to moderate all the ideas into one show. I would never tell an artist what to do, unless I’m designing the costumes myself and have an assistant.

What is it like working with conductors?

I start working with the conductor early in the process, well before the orchestra comes. I’ve only done six operas, so I don’t have a huge amount of experience and it’s useful when the conductor says something about the music that helps me know how to stage it, or something about the singers. It’s important to collaborate with the conductor while I’m still developing the staging, to avoid trouble later when we get to the stage. I’ve been lucky always to have had very good conductors who are collaborative, respectful and interested.

How do you help singers with their acting?

Every opera involves different methods. With Antikrist, none of the characters have a psychology, so it’s more about images and attitudes. That requires different directing than Gianni Schicchi, where it’s as if the characters are in a movie and have chamber theatre dialogue. You have to go into their psychology, for example, ‘You say this because you have to hide this information, so you should move like this…’ You have to understand the method of the play or opera and lead the singers or actors to where they understand their character, or if they don’t have a character, they understand the image. You lead them to where they understand the scene and feel comfortable with it.

My job is to direct the singers and help them with the movement and emotionality of their character. I would never comment on their singing: I would go to the conductor, just as if the conductor has notes about the acting, they would come to me.

Not all singers are talented actors, but there’s always a way to make them look good, with lighting, or setting the scene around them. The job of the director is to protect the singers and actors, and to make them look as good as possible. You don’t want your singer to be perceived as a bad actor. It’s your responsibility. There aren’t bad actors, only bad directors.

How do you work with production teams?

I want to know everyone’s name and function. It’s a matter of respect. I’m not only working with the actors and singers: I’m working with the whole company, which is much more than the artists. There are around 800 people in a big theatre and only 15 of them are the actors and singers.

A theatre is only as good as its workshop. A frustrated theatre team that doesn’t feel involved will at some point produce bad productions. The quality of paintings and costumes will get worse. The more you involve people, appreciate their work and show them that the theatre doesn’t function without them, the better the work they make. This reflects back to the auditorium and you get better audiences because when they watch, they feel it has a good production team. You can tell by the applause. If everyone is happy during a production, the audience will be happy. This is a mystical alchemy.

How do you make sure the team is happy?

The director and conductor are the key characters. If they are in a bad mood and show it to everyone, they are responsible if people become unhappy. Being respectful to each other can be a challenge because we are working so hard under pressure. But there are many factors involved: the intendant, the artistic director, how artists are chosen, diversity, fair payment.

There are many big elements that can build a good environment and many little things can destroy it. At every corner there is danger that the work might not be good, and not just with the singers. I expect artistic teams to prepare well so that they don’t waste resources. The money is getting less and less. People say that an artist must be free to realise their set design, but spending resources in a meaningless way is not artistic freedom.

What role does opera have to play in the future?

I don’t believe that art changes the world. That is the romantic idea of artists who think they’re important, but they are not. If the world is in good shape, you will see it in the opera, so the more harmony, prosperity and peace there is, the more time and money people have to enjoy themselves and find meaning in opera houses and theatres. During economic crises, civil war and conflicts, there isn’t much time for the arts.

Of course, there is the art of crisis, and in a crisis sometimes art becomes important. In Iran, if you go on stage and take off your head scarf and people start to clap, you will be arrested. We don’t have that dimension in Western Europe, so there is no danger when we do art. I prefer no danger and good art, and I hope I will not be forced to become more political and be endangered as an artist.

Ersan Mondtag's double bill of Gianni Schicchi and L’heure espagnole opens on 7 February.